Fear Thy Neighbor

The third blog of the Tempers & Truths Series by the Vidas Robadas team, exploring fear and faith in the context of violence, politics, and advocacy.

Last month, Minnesota experienced horrific shootings that led to the deaths of state Rep. Melissa Hortman and her husband and wounded state Sen. John Hoffman and his wife. While the exact motive of the shooter is still unclear, according to Minnesota leaders and law enforcement officials, the shootings appear to be politically motivated.

The events come as a stark reminder of how American political culture has changed in recent years. It is news to no one that political violence is on the rise in the U.S., as can be seen by the dozens of articles covering the trend. In the past year, there have been two assassination attempts on Donald J. Trump, two Israeli Embassy employees were shot and killed outside the Capitol Jewish Museum, an arsonist set fire to the Pennsylvania governor’s mansion, and a Tesla Cybertruck exploded in front of a Trump hotel. And these events do not make a holistic list.

I think it is safe to say that many, including myself, thought political violence was not something the United States was particularly susceptible to. Many thought that it was relatively safe to be a politician in America. For that matter, I’m sure many thought that no one would ever shoot up an elementary school. Yet, here we are in a situation where Americans are facing a lot of uncertainty, potential violence, and fear.

While this might feel like a new, scary moment in our history (which it is), many politicos and journalists are quick to point out that this is not the first time Americans have seen heightened levels of violence. The civil rights movement was riddled with violence, including but certainly not limited to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr, and just a few years before that, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Even further back, we have the American Civil War, the ultimate culmination of political unrest and violence. The U.S. has a checkered past with political violence, which has been discussed in multitudes.

What I specifically want to draw attention to is the connection between this surge of political violence and the broader issue of gun violence. Gun culture is simultaneously indicative of and influencing the larger political moment. This can be seen in the topic's polarizing nature, in its glorification of vigilantism, and as being the most prominent means to enact political violence.

People are afraid to talk about guns. It is an extremely polarizing issue that is often deemed inappropriate for conversations around the dinner table. There is the perception that guns and violence prevention are diametric. Politicians, public media, and the gun industry reinforce this idea, making it seem like any form of compromise or collaboration on either end of the issue is an existential betrayal. Similar to most political topics, it feels as though you are either on the team or opposing.

Firearms are also a tool that creates fear and, conversely, is sought out as a solution to fear. It has been rigorously documented that firearms sales in the U.S. increase when people are afraid. After mass shootings garner national attention, gun sales dramatically go up for the following month or so. Gun sales also tend to increase around presidential elections.

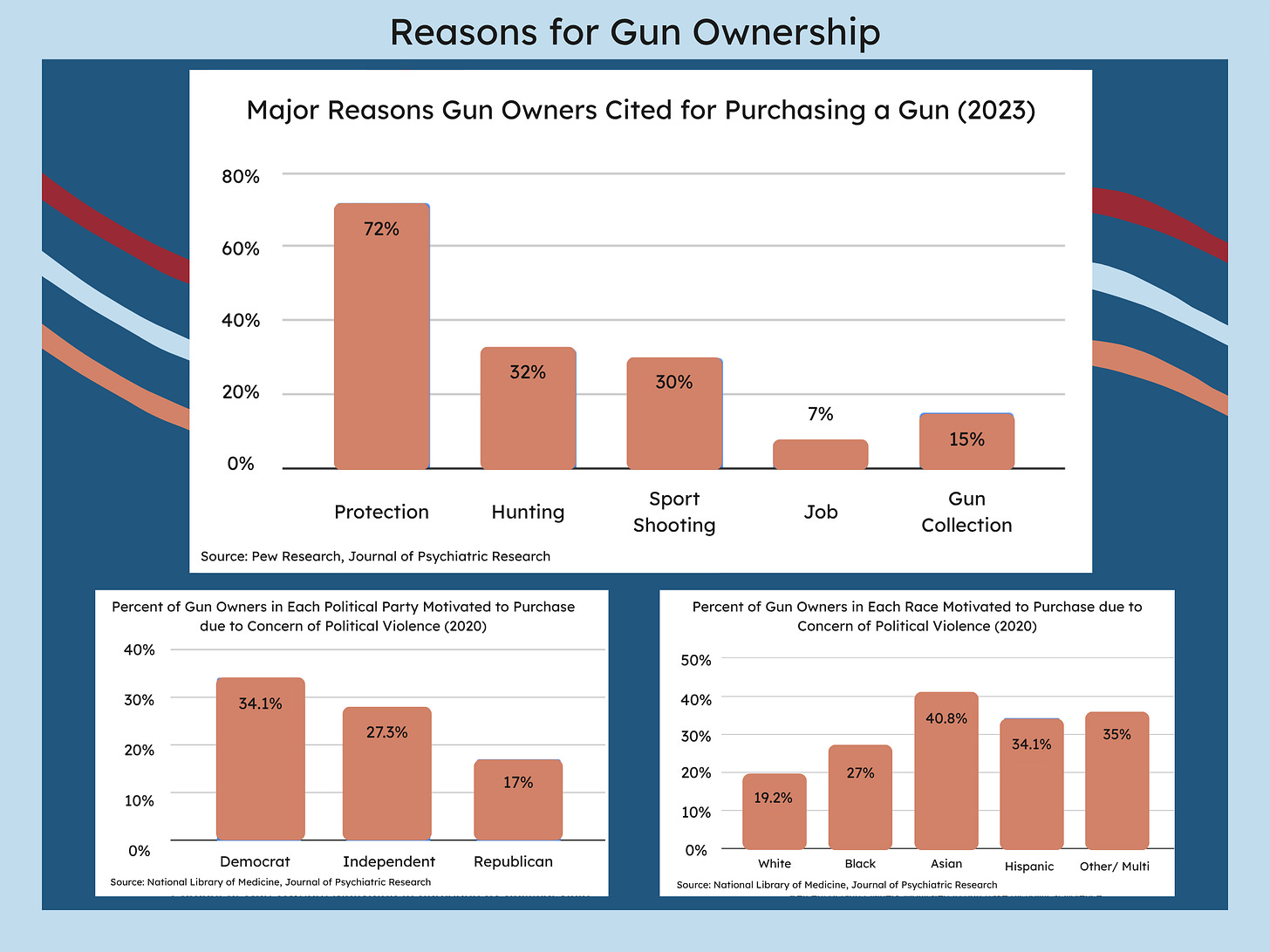

The demographics of those buying guns are also more diverse than most would realize. While super owners (those who have a large collection of firearms) continue to be dominated by middle-aged, conservative, white men, there has been a significant increase in gun purchases by self-identified liberals, urban women, and communities of color. Across the political spectrum, the dominant reason people are purchasing firearms is for protection. The stockpiling of arms by one group leads to an increase in arming by the other. In simpler terms, people get scared, so they buy guns, which makes other people scared, so they buy guns. This cycle is a destructive civilian arms race that can’t help but increase the likelihood of political violence.

After every mass shooting or act of political violence, American media obsessively dive into the psyche and motives of the perpetrators, which is understandable. It seems pertinent to understanding why and how the incident occurred. But motive is complicated, especially with someone unstable enough to attempt such horrific acts. As a society and in such deep dives, we tend to hyperfixate on someone’s political leanings, which feeds into the “us versus them” mentality. However, I believe that when examining political violence and violence prevention in general, it is perhaps more essential to understand why someone feels compelled to choose violence.

In the context of political violence, one can assume that some of the reasoning for such an act is rooted in a distrust and fear of the current political structure. There are other factors at stake, such as the perpetrator's mental stability, past personal history, and current life circumstances. But, notwithstanding these factors, political violence is done because there is a belief that other means of political change are either ineffective or unavailable. There is no faith in our institutions, so vigilantism is the solution. That distrust in government, fear of your neighbor, plus a growing civilian armament, is a very frightening mix.

However, just like gun culture can help us examine factors contributing to political violence, the violence prevention movement can help us identify potential remedies. As a part of Vidas Robadas, Texas Impact’s gun violence prevention and awareness campaign, we hold events to accompany the display of the t-shirt memorials representing gun violence victims. Depending on the location that is hosting the memorial installation, we might host a panel discussion with local experts to help the community better understand the multi-faceted nature of gun violence and proven ways to address it.

At the end of last year, we held one such panel at a house of worship in Austin that had a politically mixed congregation. We brought in a panel that included medical experts, lawmakers, and representatives from Community Violence Intervention (CVI) programs. The panelist covered a variety of topics, including their own personal experiences with gun violence, the difference between gun homicides and suicides, and, importantly, an idea in the CVI representative referred to as the “ecosystem.”

The “ecosystem” describes a critical part of the strategy of CVI programs, which involves building credible relationships among stakeholders and affected neighborhoods. Often, urban areas that see the highest levels of gun violence are black and brown neighborhoods that have historically experienced disinvestment and governmental neglect. As shared by stories from violence interrupters (individuals in CVI programs who identify and intervene in situations that could become violent), members of those neighborhoods do not trust easily. They have been burned and neglected, and rarely see opportunities for change.

Violence interrupters, which are also called credible messengers, have to work to establish relationships within these communities and prove to them that they are actually there to help. When they can do so successfully, they are fostering faith—a complete trust that there are institutions and people who will support them. By creating faith, a term that captures the profound strength needed for real and long-lasting change, communities and individuals can choose better solutions to their fears than violence.

A few days after that panel discussion, while revisiting that same congregation, a married couple who attended the church thanked Texas Impact for bringing Vidas Robadas and the panel to their congregation. The couple (who, out of respect for their privacy, will remain nameless) had very different views on guns. The wife is a nurse, and the husband is a firearm enthusiast, and guns were a point of tension between them.

After hearing the panel and participating in Vidas Robadas, they had a breakthrough in their understanding of one another. The husband, influenced by new information like the prevalence of suicides and susceptibility of children to accidental shootings, became open to prevention methods like safe storage, which in turn made his wife more comfortable with guns being in their home. Months later, the husband even volunteered at our Gun Violence Prevention Advocacy Day at the Texas Capitol. By engaging in a good-faith effort to talk about how we can make our communities safer, we created an opportunity for people to connect outside of our rigid, bipolar political culture, and as a result, a married couple was not afraid to have a hard conversation.

Now, conversations alone won’t solve America’s gun violence epidemic or rising political violence. They need to be backed by real policy change at every level of government. But in order to achieve policy change, we also have to address our gun culture. In order to do that, we need to address why people are afraid of each other. We have to work to establish faith that things can be better, and use every avenue available for political and cultural change before resorting to violence. If we accept that politics is a zero-sum game and that violence is the best tool for winning it, then we will create a reality that is far more frightening.